Description

Painted with Gosu Blue Imperial Palette

From our Japanese Satsuma collection, we are pleased to present this good sized Japanese Gosu Blue Satsuma Vase 薩摩. The vase is potted in earthenware with a wide body and short neck, decorated in deep gosu blue and polychrome enamels with gilt details.

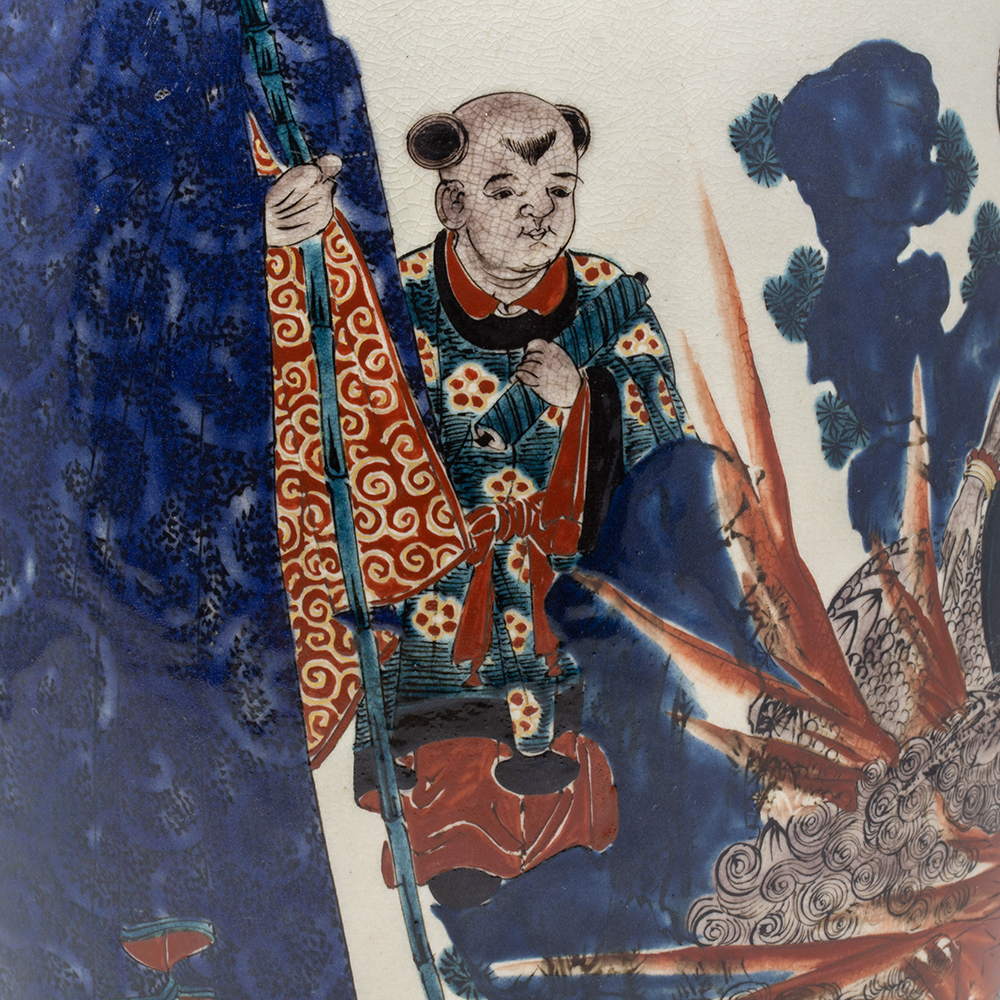

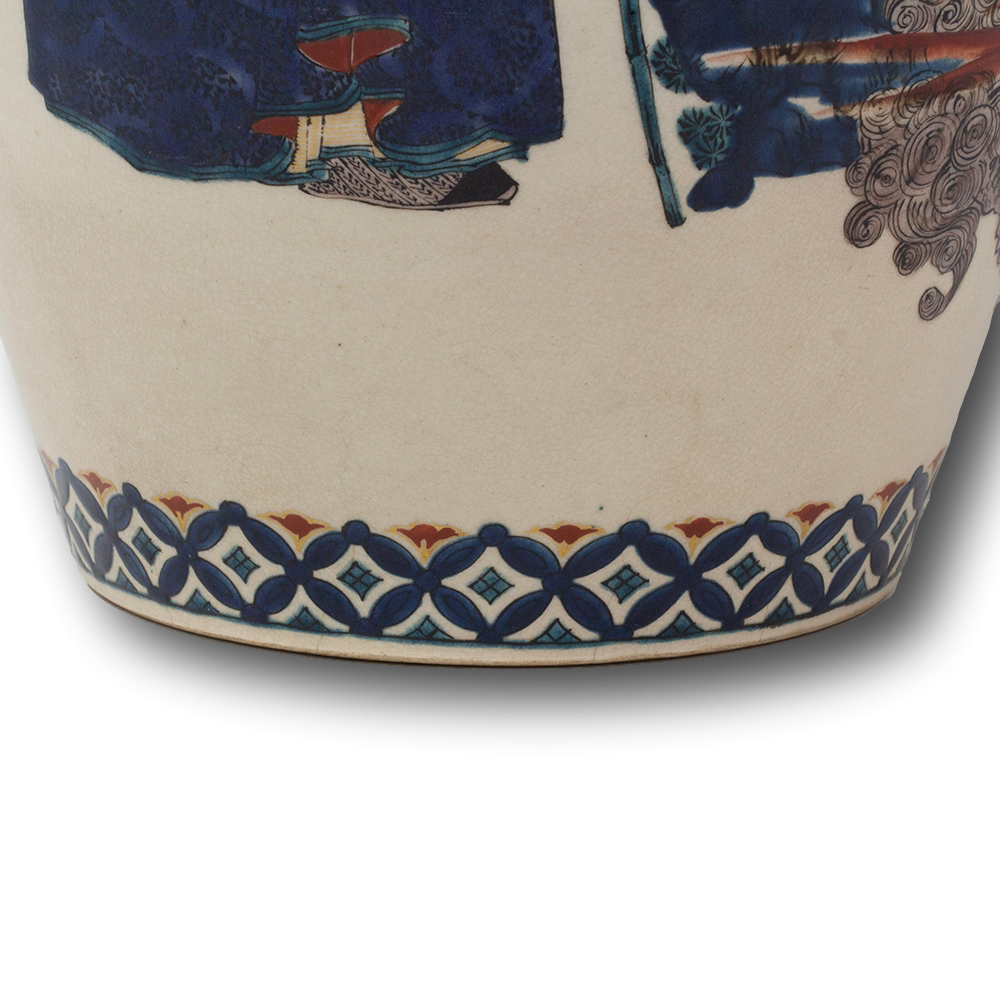

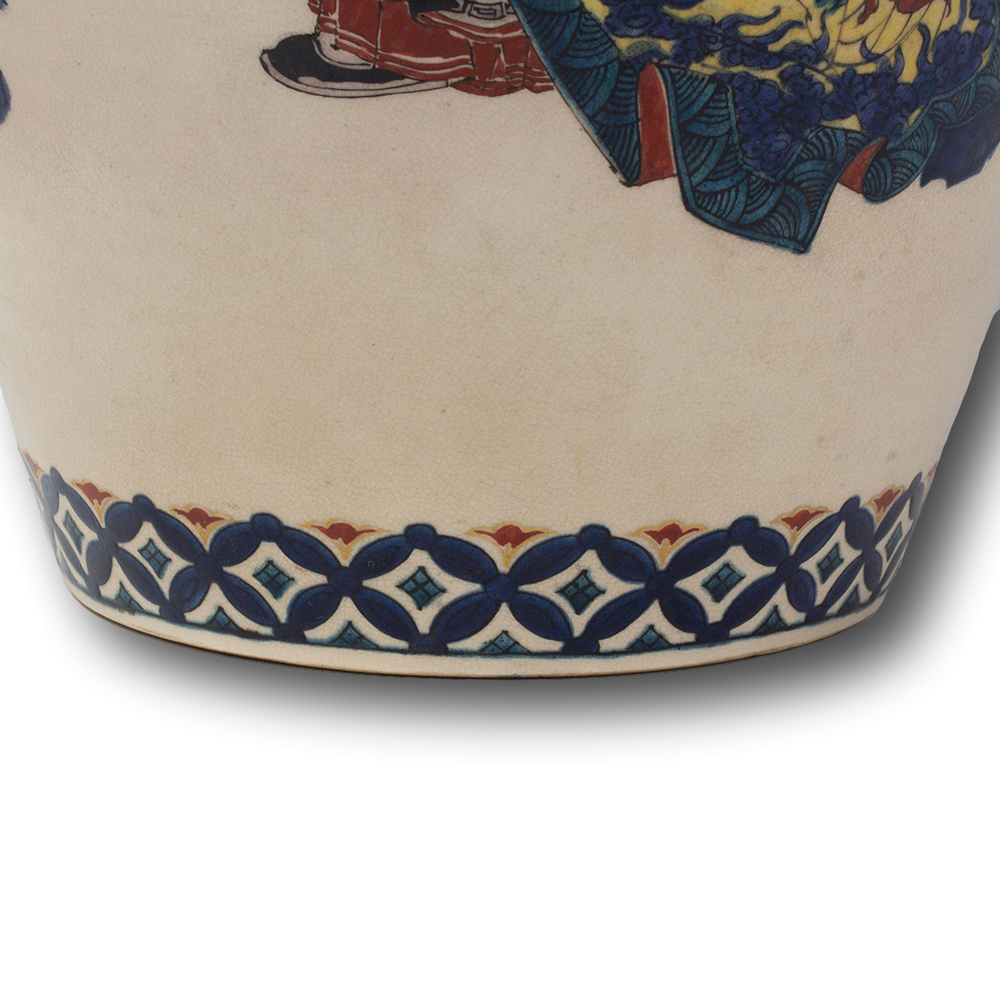

The rim is painted with a border of lappets featuring stylised foliage and paulownia flowers, while the base is banded with a linked cash (shippo-tsunagi) motif. Around the body, a continuous scene depicts five Rakan (羅漢, also known as Arhats), Buddhist disciples revered for their wisdom.

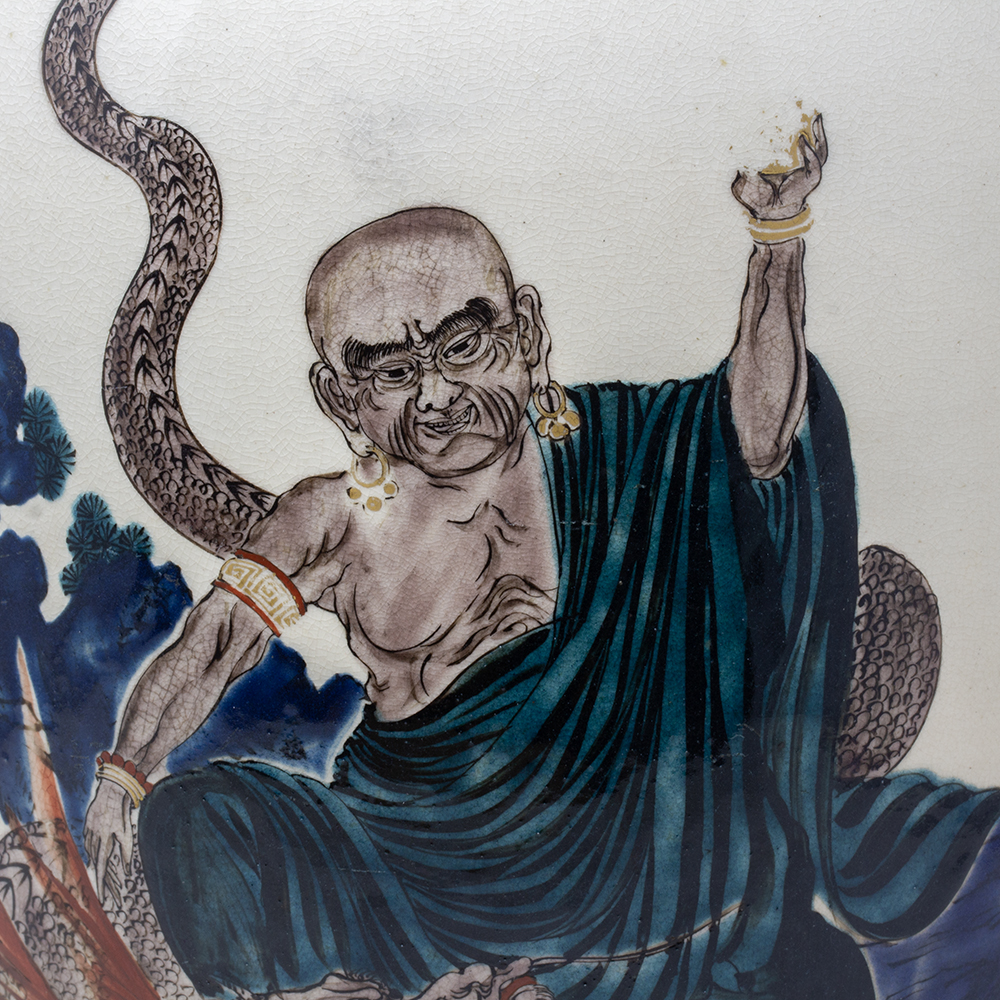

One figure is seated on a bamboo chair holding prayer beads, distinguished by long flowing eyebrows. Another wears a dragon-patterned robe and reads a scroll, while a third leans on a bamboo staff beside a child assistant. The final figure raises his hand aloft, performing a ritual with a dragon emerging at his feet. The scene is finely painted with expressive features and rich colours, bringing depth and narrative to the composition.

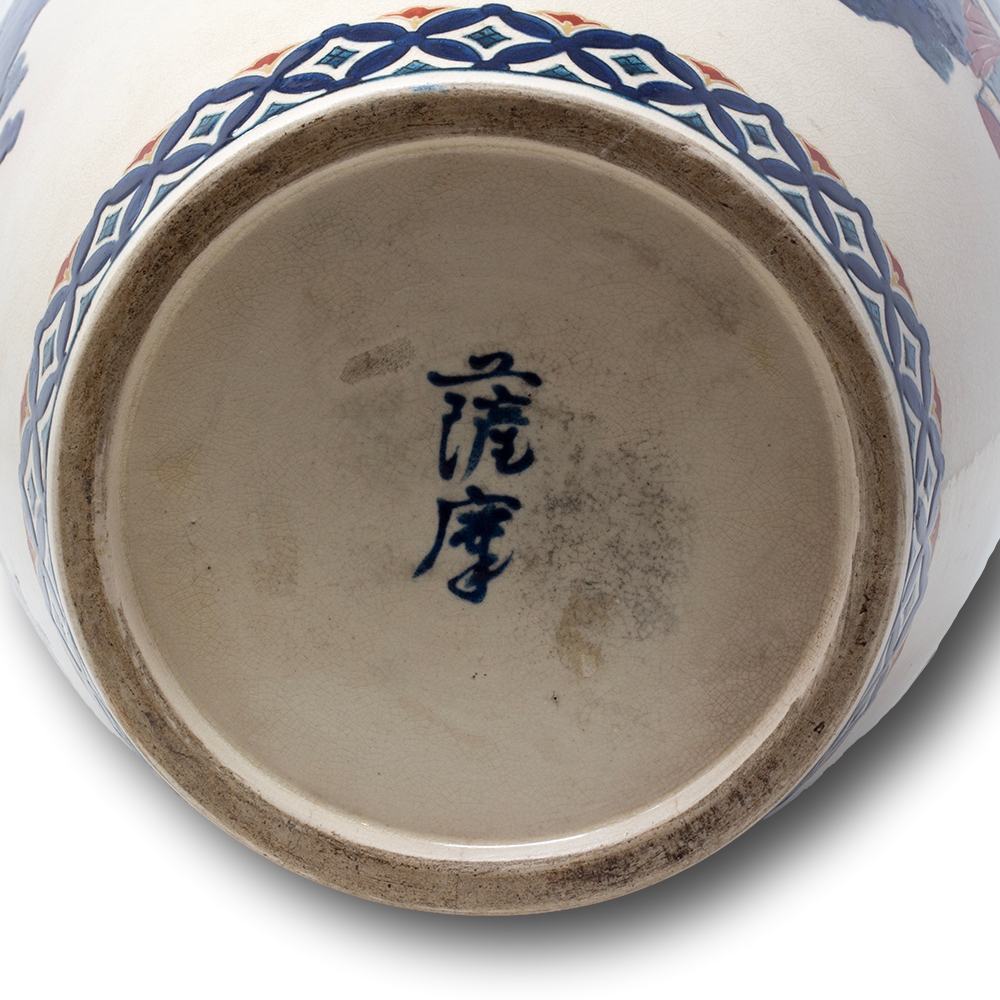

The base is signed 薩摩 (Satsuma) and the vase dates to the early Meiji Period (1868–1912), circa 1880. A striking and good example of Gosu Blue Satsuma with figural subject matter of Buddhist importance.

Rakan 羅漢

also known as Arhats, are revered figures in Buddhist iconography, particularly prominent in East Asian art, including Japanese, Chinese, and Korean traditions. The term “Arhat” (from Sanskrit) translates as “one who is worthy” or “venerable,” while “Rakan” is the Japanese reading of the same concept. These enlightened disciples of the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, are venerated for having attained nirvana through rigorous practice and deep spiritual insight.

In visual culture, especially in Japanese Meiji-period ceramics, scrolls, and temple statuary, the Rakan are often portrayed as eccentric, otherworldly ascetics – each with distinctive physical features, gestures, or symbolic objects that reflect their spiritual journey or miraculous abilities. While their forms can range from serene and meditative to wild and expressive, Rakan are unified by their profound spiritual attainment, often depicted in mountainous landscapes, celestial gatherings, or in close proximity to tigers, dragons, or clouds, signifying their mastery over nature and illusion.

A traditional set of Sixteen or Eighteen Arhats is associated with East Asian Buddhist art, with later traditions expanding the group to include 500 Rakan, each with a specific narrative or miracle associated with their path to enlightenment. This richness offers artists and craftsmen the opportunity to depict a wide variety of human expressions, making Rakan popular subjects for Satsuma ware, temple murals, and lacquer panels.

Unlike bodhisattvas who delay their own enlightenment to help others, Arhats are seen as those who have completed their spiritual path embodying the ultimate goal of early Buddhist practice. They serve as guardians of the Dharma (Buddhist teachings), often portrayed as protectors against ignorance and corruption.

MEIJI PERIOD (1868-1912)

The Meiji era marked Japan’s transformation into a modern nation and a golden age of decorative arts. With the end of samurai rule and Japan’s opening to the West, artisans produced works of exceptional quality for both domestic and international audiences. Supported by the government through world fairs and Imperial commissions, Japanese lacquerware, cloisonné, satsuma ceramics, bronzes, and ivory carvings reached collectors worldwide. Many leading artists of the time, including Makuzu Kozan and Namikawa Yasuyuki, were honoured as Imperial Household Artists, ensuring the Meiji period remains one of the most celebrated eras of Japanese art.

For further information please see our article Japanese Meiji Period: Art, Collecting, and Cultural Transformation.

SATSUMA WARE

Satsuma ware originated in southern Kyūshū around 1600 and developed into one of Japan’s most recognisable ceramics. Early Ko-Satsuma pieces were rustic, dark-clay wares made for everyday use, while the later Kyō-Satsuma style became famous worldwide during the Meiji period.

Characterised by ivory crackled glaze, delicate overglaze enamels, and lavish gilding, export Satsuma appealed strongly to Western collectors. Designs often feature landscapes, flowers, figures, and scenes from Japanese life and mythology. Renowned artists such as Yabu Meizan, Ryozan, and the Kinkōzan workshop produced some of the finest examples, which remain highly sought after today. Genuine Satsuma can often be identified by the Shimazu crest, artist signatures, or the mark “Dai Nippon” used during the Meiji era.

For further information on the history of Satsuma Wear please see our article Japanese Satsuma Ware.

Gosu Blue

refers to a deep, rich cobalt blue pigment traditionally used in Japanese ceramics, particularly in Satsuma ware during the late Edo and Meiji periods. The term “Gosu” (呉須) itself is derived from the Chinese word for cobalt pigment and was introduced to Japan through Chinese porcelain traditions.

In Japanese ceramics, Gosu blue was typically applied under or over the glaze, depending on the intended effect. It was especially popular during the Meiji period for export wares, where potters used it to create striking contrasts with gold and cream backgrounds. On finely decorated Satsuma pieces, you’ll often see Gosu blue used in patterned borders, robes, or backgrounds. It appears almost inky or navy when thickly applied and, can be softer or lighter in finer detailing. Unlike the soft, muted tones of earlier Japanese pottery, Gosu blue brought a bold vibrancy to Meiji Period ceramics, and collectors often look for it as a sign of high-quality decoration.

Paulownia Seal

is a symbol that took inspiration from the Paulownia tree. It was used by the Toyotomi clan who ruled over Japan before the edo period. It is written in Japanese history that when a paulownia leaf falls, the world’s autumn is known. The ‘world’s autumn’ implies the changing of the dynasty. Since paulownia leaves are the crest of the Tyotomi family that ruled Japan in the sixteenth century and was ruined by the Tokugawa, the word hito ha (“one paulownia leaf”) implies a sort of sadness. The Paulownia seal is used today as the official emblem of the Japanese government.

Earthenware

is one of the oldest types of pottery, made from clay fired at lower temperatures than stoneware or porcelain. The result is a porous, slightly coarse material that’s often finished with a glaze to hold liquids. It’s been used across the world for thousands of years to make everything from cooking pots to decorative ceramics. Because of its versatility and ease of shaping, earthenware became a go-to material for both practical household items and artistic pieces. It’s still widely appreciated today, particularly for its warm, natural texture and traditional aesthetic.

Shippo-tsunagi

Seven treasures – is a traditional Japanese geometric pattern made with overlapping quarters of the same-sized circle.

MEASUREMENTS

38cm High x 22cm Diameter (15 x 8.66 Inches)

CONDITION

Very Good, minor rubbing most notable to the hand of the raised Rakan.

With every purchase from Jacksons Antique, you will receive our latest product guide, certificate of authenticity, full tracking information so you can monitor your shipment from start to finish and our personal no-hassle, money-back policy giving you that extra confidence when purchasing. Don’t forget to sign up to our free monthly newsletter for 10% off your first online purchase.